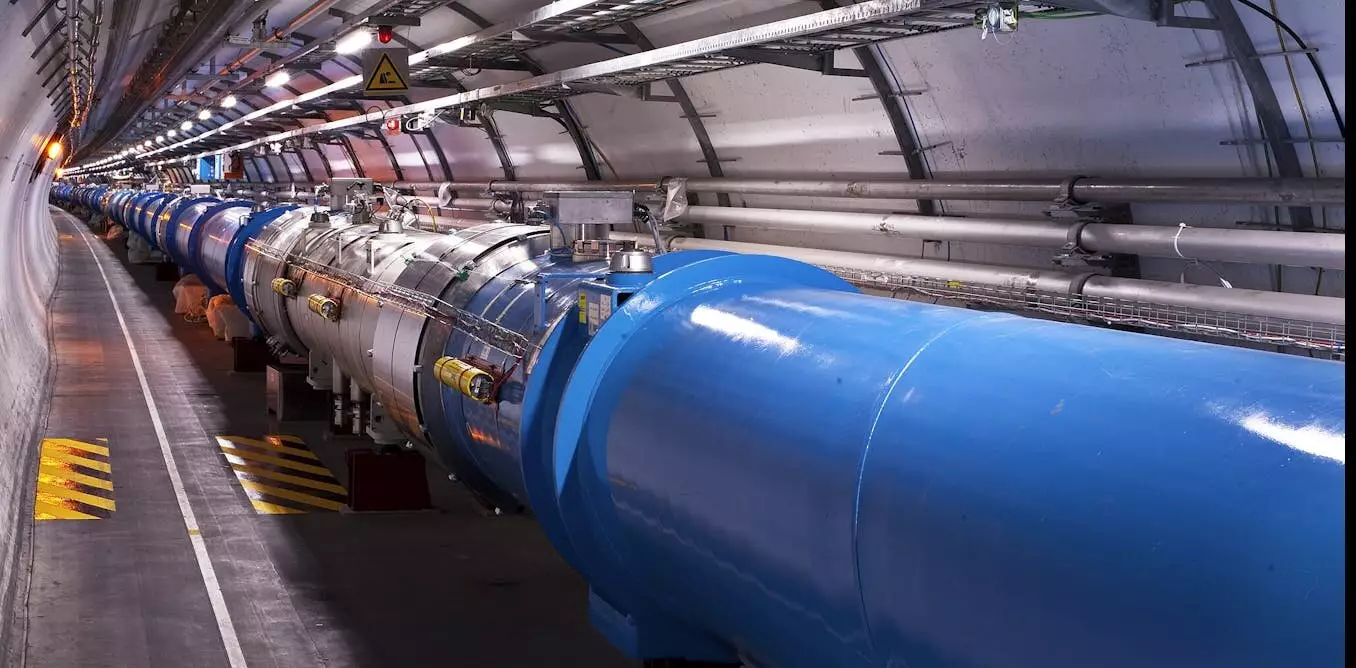

At CERN, the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) is a complex machine that requires a careful reset every year to ensure accurate data collection. Engineers and physicists at CERN take several weeks to calibrate the collider and its experiments to smash protons at the highest energy levels ever reached. This process is crucial for studying the universe’s most compelling mysteries by exploring the world of subatomic particles, the fundamental building blocks of everything around us.

During the winter months, the collider and its experiments hibernate to undergo necessary maintenance. This downtime allows the teams at CERN to replace components, install new pieces, and ensure that everything is in working order. Additionally, running the machines during the winter months when electricity costs are higher is avoided. When spring arrives, the teams prepare the LHC and the experiments for a new season of data gathering.

The process of waking up the LHC begins with testing the particle detectors while the accelerator is still asleep. This initial phase involves using cosmic rays, which are subatomic particles created when energetic particles from space interact with atoms in the atmosphere. These cosmic rays help train the sensors and verify that everything is functioning correctly. However, due to the random and sparse nature of cosmic rays, additional tests using subatomic splashes are conducted to ensure the detectors are working as expected.

The LHC accelerates protons through a series of pipes with magnets that steer the particles. Any protons that stray off track are stopped by collimators, creating a “beam splash” of particles. This beam splash is used to test whether all the detectors in the experiment react correctly and in sync, as well as to verify their data recording capabilities. While most detectors are ready to receive new data, specific detectors, such as the Tile calorimeter in the ATLAS experiment, require additional testing.

The Tile calorimeter, which measures the energy of particles, requires precise calibration using muons. Muons are particles similar to electrons but heavier, making them ideal for testing particle detectors. Collimators are used to generate muons by pushing them gently into the protons’ path, creating particles that move parallel to the accelerator pipe and hit the ATLAS experiment horizontally. Dedicated sensors track these muons as they pass through all the calorimeter’s tiles, ensuring accurate data collection.

Once the LHC and its experiments are calibrated and ready, protons are accelerated to their maximum energy levels and made to collide with each other. After a series of tests lasting around 10 weeks, a new season of data gathering begins. This process of using subatomic splashes to restart experiments showcases the meticulous precision and dedication of the teams at CERN in their pursuit of scientific discovery.

Leave a Reply