Microplastic pollution has become a global environmental challenge, capturing public attention through powerful imagery of wildlife entangled in plastic debris and pristine beaches marred by tiny particles. While it’s common to envision significant oceanic plastic waste as overwhelmingly visible, substantial quantities remain hidden beneath the surface, creating a troubling disconnect. New clarifications in research, particularly focusing on the North Sea, reveal critical insights into these overlooked microplastic sinks.

Every year, approximately 12.7 million tons of plastic enter the world’s oceans, primarily from terrestrial runoff via rivers, alongside contributions from fishing, shipping, and aquaculture. Despite this immense influx, the visible plastic in ocean surface waters often fails to convey the true extent of the issue. This stark contrast underscores the complexity of microplastic distribution and the pressing need to explore deep into marine ecosystems for a more comprehensive understanding.

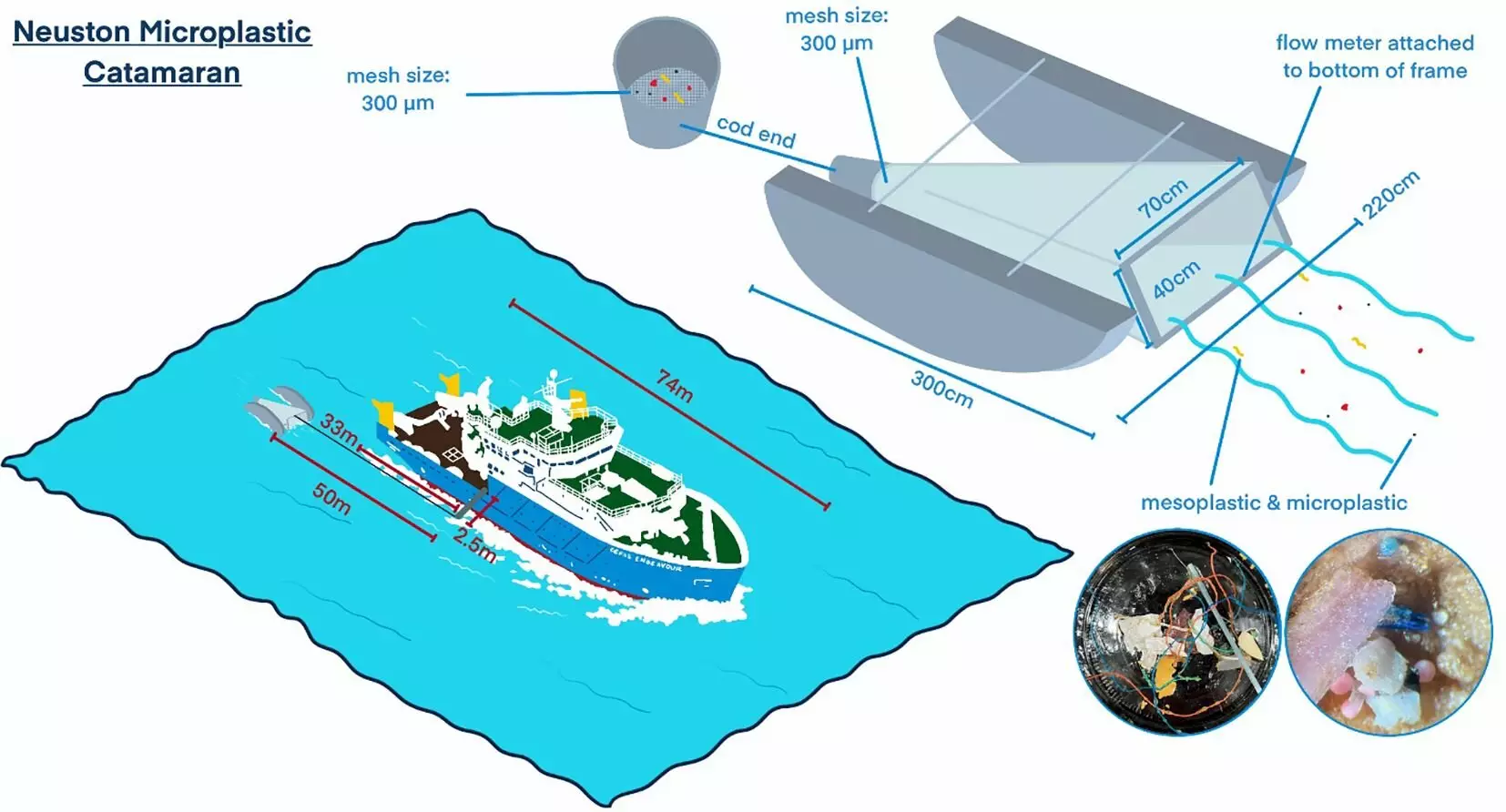

Recent studies, particularly one published in Frontiers in Marine Science, have identified certain marine areas, like the North Sea, as significant reservoirs for microplastics—small plastic particles measuring less than 5 mm that stem from the breakdown of larger plastic debris. Researchers under the guidance of Dr. Danja Hoehn utilized a specialized Neuston Microplastic Catamaran to effectively capture surface microplastic data across the North Sea. This innovative equipment collects plastic as it floats on the ocean surface—where microplastics initially enter the marine environment—before they sink or disperse.

Noteworthy Findings from the Research

The findings of this groundbreaking work revealed alarmingly high concentrations of microplastics within the Southern Bight of the North Sea, with measurements reaching over 25,000 items per square kilometer. In contrast, offshore Scottish waters showed lower averages, highlighting a concerning concentration gradient in this marine environment. Polyethylene emerged as the dominant plastic type, making up 67% of the findings, with significant proportions attributed to polypropylene and polystyrene as well.

Analyzing microplastic types sheds light on the sources and potential impacts of plastic pollution. The ubiquitous presence of polyethylene, often found in shopping bags and containers, points to everyday consumer behavior as a significant contributor. Despite bans on microbeads in cosmetics and personal care products in the UK, persistent traces suggest transport mechanisms, such as ocean currents, are bringing pollutants from other countries into UK waters.

Color analysis of the collected plastics indicated a wide variety of hues, with white consistently emerging as the most common color, likely attributed to the prevalence of plastic bags and packaging. This color distribution, alongside location-specific heat maps, revealed hotspots near the East Anglia coast, characterized by exceedingly high concentrations of microplastic debris.

While England’s findings are concerning, they are still lower than other global hotspots. Previous studies indicated astounding microplastic densities off the coasts of northwest Spain and Portugal, and even more alarmingly, a staggering one million items per square kilometer in the Canary Islands. This disparity highlights the global urgency to address the escalating scale of oceanic plastic contamination, emphasizing that effective remediation and prevention approaches must extend beyond local efforts.

The struggle against plastic pollution is met with various national and international initiatives aiming for substantive change. In the UK, strategies like the Marine Strategy seek to embed microplastics indicators within marine sediments. Similarly, international frameworks, such as the UN Environmental Agency’s goal for a legally binding agreement to eliminate plastic pollution by 2040, signal the collective recognition of this pressing issue.

As the global demand for plastics surges beyond 400 million tons annually, understanding and addressing microplastic pollution is imperative. Concrete actions rooted in research and collaboration hold the potential to safeguard oceans for future generations. With persistent public and governmental engagement, combined with innovative scientific studies, we may finally turn the tide against the tide of plastics engulfing our oceans.

Leave a Reply