When faced with a cardiac arrest, time is of the essence. The difference between life and death can often come down to immediate action; specifically, the administration of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). This vital emergency procedure helps maintain blood flow and oxygenation to the brain and vital organs until professional help arrives. However, recent research sheds light on a concerning trend: bystanders frequently hesitate to perform CPR on women compared to men. This hesitance not only raises questions about why this disparity exists but also highlights the dire need for a reevaluation of training methods aimed at equipping individuals to respond effectively in emergencies, regardless of the victim’s gender.

A recent study from Australia bolstered concerns about gender biases in CPR responses. Analyzing data from 4,491 cardiac arrest incidents, researchers found that bystanders were significantly more likely to initiate CPR on men (74%) than on women (65%). Such discrepancies inevitably lead to questions about societal perceptions surrounding women and emergencies. It raises the possibility that factors such as societal gender roles, stereotypes, and discomfort with the female anatomy may play a role in this discrepancy.

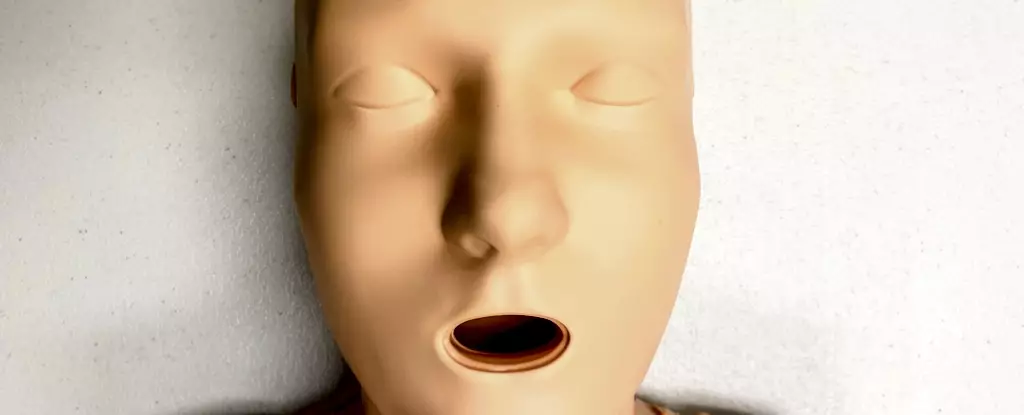

While studies indicate that female anatomical features do not alter the CPR techniques required, it appears that the visual representation of these techniques significantly impacts willingness to intervene. Training mannequins, commonly used in CPR courses, predominantly lack breasts. An alarming 95% of available CPR training manikins are flat-chested, which inadvertently endorses a male standard and fails to prepare bystanders for real-life scenarios involving female victims. The absence of realistic representation can distort perceptions of how to recognize and respond to a cardiac arrest, particularly in women.

Cardiovascular diseases are the leading cause of mortality for women worldwide. Statistics reveal that women face a significantly higher risk of receiving inadequate CPR in emergencies, resulting in a 10% lower likelihood of intervention compared to their male counterparts. Even when women do receive CPR, they tend to have poorer outcomes, including higher rates of brain damage following cardiac arrest. These statistics underscore the need for urgent reform in training methodologies and response strategies.

Moreover, the healthcare system’s treatment of women, as well as transgender and non-binary individuals, often perpetuates disparities. Research indicates that their symptoms are frequently dismissed or misdiagnosed, adding layers of complexity to effective intervention. The hesitancy to render assistance may stem from fears of misinterpretation, accusations of harassment, or concerns over the physical touch required during resuscitation. Such societal apprehensions could lead to a cycle where women, and marginalized genders, receive less effective emergency care.

A critical examination of CPR training involves the understanding of training mannequins. The dominance of male and flat-chested mannequins diminishes the potential for participants to rehearse real-life scenarios effectively. Research indicated that only 25% of the CPR manikins available on the global market in 2023 were marketed as “female,” and a mere one had breast representation. This imbalance signifies that the majority of CPR training continues to cater primarily to male representations, which is a detrimental oversight.

This lack of diversity extends beyond gender representation. While 65% of CPR manikins boast multiple skin tones, only one model represents larger body types. This limited diversity in training tools disregards the very real variety of physical forms present in emergency situations, which could dissuade bystander intervention and reinforce biases in life-saving responses. The training industry must acknowledge and address these inadequacies by providing more appropriate and realistic training resources that encompass a range of body types and genders.

The ultimate goal of CPR training must be to empower individuals to recognize and act on cardiac arrest indicators without hesitance. Critical signs include unresponsiveness and abnormal breathing patterns. To execute effective CPR, the responder should place the heel of one hand in the center of the victim’s chest, interlock the fingers of the other hand, and press down firmly at a pace of 100-120 compressions per minute.

Moreover, while it is important to discuss the potential need to remove a bra for effective defibrillation, the urgency of administering CPR should remain paramount. Delays can substantially reduce survival chances, so responders must be trained to prioritize action above hesitation fueled by discomfort or misconceptions.

Addressing the evident biases in CPR responses requires a comprehensive revision of training methodologies that reflect the real-world diversity of individuals at risk of cardiac arrest. Enhancing the inclusiveness of training resources and supporting broader education around women’s cardiovascular health are essential steps toward fostering an environment where all individuals feel equipped to respond, ultimately saving lives and bridging the gender gap in emergency responses.

Leave a Reply