Shock experiments pose as a vital tool in modern science, especially in fields such as material science and planetary exploration. These experiments help researchers understand how materials respond under extreme conditions—like the immense pressures generated during meteorite impacts. In recent years, advancements in technology have opened up new avenues for exploring the thermal behavior of materials post-shock. Despite significant progress, key questions regarding the thermal states following shock events remain inadequately addressed.

The research conducted by scientists at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL), recently documented in the Journal of Applied Physics, offers groundbreaking insights into this intriguing area. Utilizing ultra-fast X-ray probing techniques, they have looked into the thermal responses of aluminum and zirconium alloyed under shock conditions. The findings reveal that materials experience much greater temperatures during shock release than previously anticipated, prompting a reevaluation of commonly held assumptions concerning their mechanical properties.

Shock waves are fascinating phenomena characterized by abrupt changes in material properties, including pressure, density, and particle velocities. As these waves travel through a substance, the physical landscape of the material alters dramatically. This transformation is not merely mechanical; it’s also deeply thermodynamic. When a shock wave interacts with matter, much of the energy is seemingly consumed by increasing the entropy and temperature of the material rather than moving it in a kinetic manner.

This characteristic of shock compression poses challenges for scientists who seek to model and understand material behavior consistently. Standard hydrodynamic models, which often rely on historic data regarding materials like aluminum and zirconium, frequently fall short of accurately portraying the complexities involved. Consequently, researchers must dig deeper to identify supplementary mechanisms that govern thermal responses during these shock wave cycles.

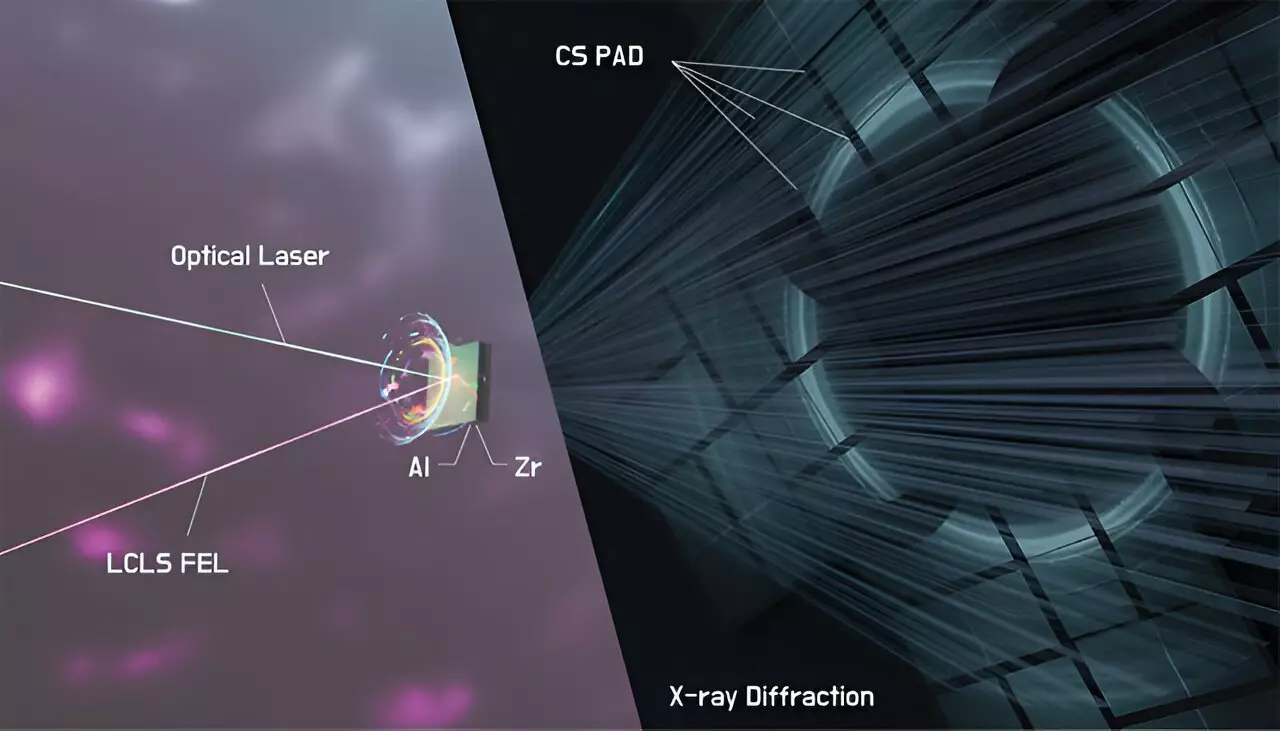

In their latest experiments, the LLNL research team applied laser shock techniques paired with ultra-fast X-ray diffraction methods to accurately trace temperature shifts in aluminum-zirconium composites. The experiments were conducted at various time intervals from the initial shock event, and the results were striking. It was found that both aluminum and zirconium underwent substantial heating, an unexpected result attributed to energy dissipation owing to inelastic deformation.

Harry Radousky, the principal investigator, emphasized the significance of this finding, indicating that the existing hydrodynamic models failed to predict the heightened temperatures accurately. The implications of this discrepancy are vast, suggesting that there exist unrecognized strain-rate-related factors that could be pivotal in shaping thermal behavior under such extreme conditions.

Moreover, colleague Mike Armstrong pointed out a crucial aspect of shock energy dynamics: a remarkable portion of the energy delivered during the shock transforms into heat rather than kinetic energy. This decay into heat is closely tied to defect-facilitated plastic work—a phenomenon that surprisingly has not received much attention in preceding studies.

The investigation results extend beyond mere academic curiosity. By uncovering the high post-shock temperatures, the study nudges the scientific community toward considering potential phase transformations occurring during shock releases. Such transformations can significantly alter the materials’ structural integrity and physical attributes.

Armstrong mentioned a compelling application of these findings in preserving the magnetic records on planetary surfaces affected by shock events. The realization that impact events can induce unexpected thermal responses opens new avenues for understanding planetary geology and the history imprinted on their surfaces.

Using the Matter in Extreme Conditions instrument at the Linac Coherent Light Source allowed the team to conclude that unexpected thermal processes—such as void formation—occur alongside shock wave interactions. The remnants of these increased post-shock temperatures indicate that conventional hydrodynamic models require significant refinement to incorporate a more comprehensive understanding of material behavior under extreme conditions.

The LLNL study represents a crucial leap in unlocking the complex interplay between shock waves and material properties. As scientists continue to push the boundaries of material science, these insights will serve as a foundation for enhancing our understanding of material behavior under extreme conditions, whether in laboratories or on distant planetary surfaces. This ongoing research highlights the importance of questioning existing models and adapting our comprehension of the natural world to accommodate new findings. The pursuit of knowledge in this domain is not merely academic—it holds the potential to reshape how we perceive and interact with the cosmos around us.

Leave a Reply