Bacteria, often vilified as mere pathogens, possess incredible capabilities that extend well beyond disease. These minuscule organisms have demonstrated exceptional potential in producing a wide variety of materials such as cellulose, silk, and even minerals—substances that hold immense value in various industries, particularly in biomedical applications, textile manufacturing, and eco-friendly packaging. Their production methods are inherently sustainable, operating at ambient temperatures and in aqueous environments. Yet, there exists a catch: while bacteria can create these materials, they do so in quantities that are far too minimal for industrial scaling.

This paradox of sustainability versus productivity has sparked a flurry of research endeavors aimed at engineering bacteria into efficient biological factories capable of yielding larger volumes of valuable materials in significantly shorter timeframes. A fascinating advance in this frontier has emerged from the creativity and scientific rigor of the research team led by Professor André Studart from ETH Zurich, who are trailblazing a new method to optimize bacterial cellulose production.

A Revolutionary Approach to Bacterial Optimization

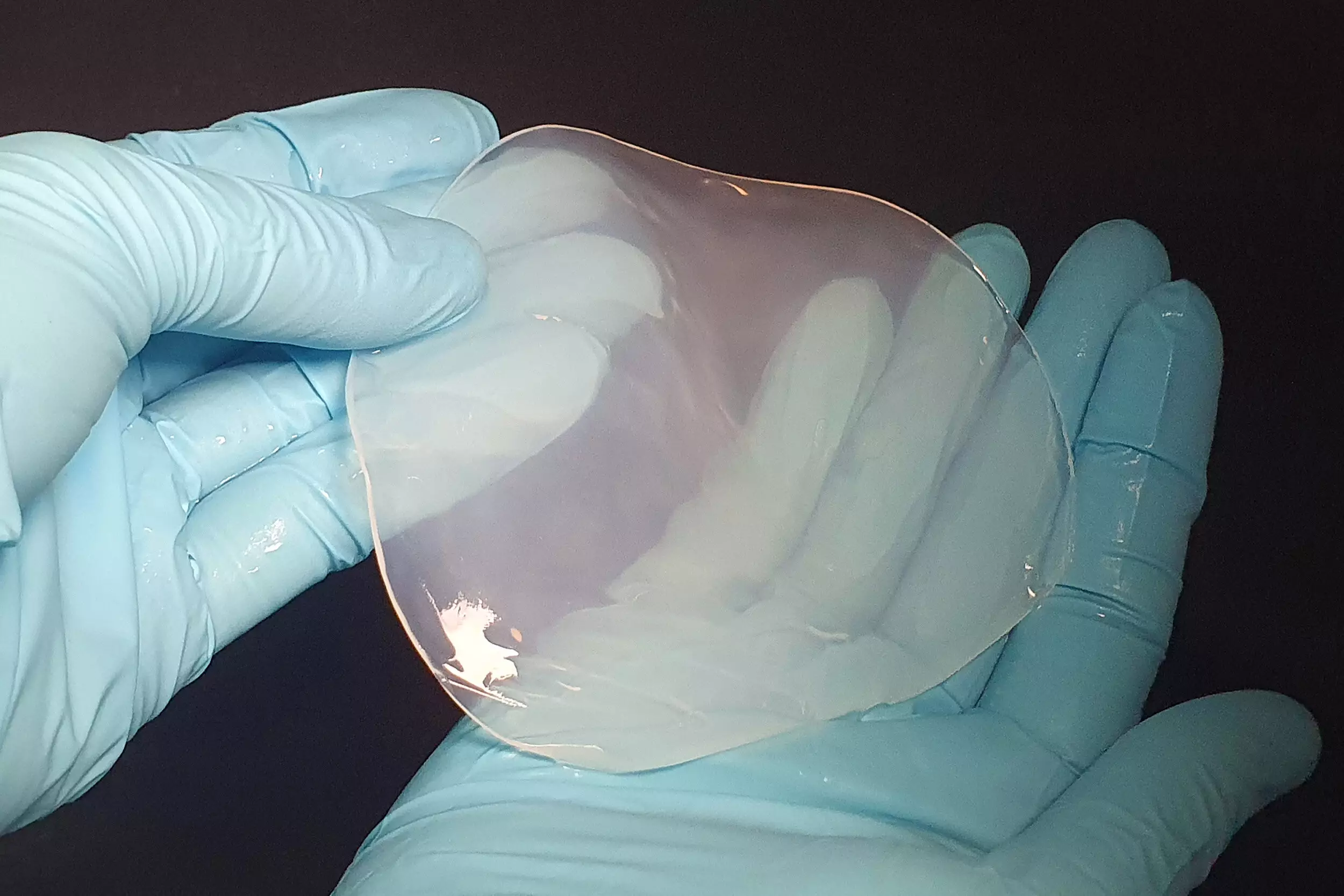

The cellulose-producing bacterium Komagataeibacter sucrofermentans serves as the centerpiece of their innovative research. This bacterium is known for its ability to naturally synthesize high-purity cellulose, a critical material that not only facilitates wound healing but can also serve as a shield against infections. The challenge, however, lies in its sluggish growth rate and surprisingly low cellulose output. In addressing these issues, researchers have explored an exciting evolutionary tactic rooted in natural selection principles to produce a wide array of bacterial variants swiftly.

Doctoral student Julie Laurent spearheaded this research, meticulously investigating how to amplify cellulose yields. By initiating targeted mutations through irradiation with UV-C light—an approach that disrupts the genetic integrity of the bacteria—Laurent cultivated an array of variants. By purposely inducing DNA damage and then preventing any natural repair processes, she allowed for mutations that could lead to enhanced cellulose production.

A vital aspect of Laurent’s methodology included an ingenious strategy using miniature nutrient droplets to isolate the bacteria during incubation. After a predetermined growth period, she employed advanced fluorescence microscopy to pinpoint which bacterial cells had triumphed in cellulose synthesis, focusing on those that produced remarkable quantities. This initial selection played a crucial role in a subsequent automated sorting process, engineered by chemist Andrew De Mello’s team, that swiftly assessed and separated the best-performing cells—scanning hundreds of thousands in mere minutes.

Transformative Discoveries and Genetic Insights

The results were astounding; the evolved variants of Komagataeibacter yielded cellulose mats almost double the weight and thickness when compared to their wild counterparts. This significant enhancement offers a glimmer of hope for increased efficiency in applications that require high-volume cellulose, thus making these advanced bacteria highly desirable for industrial use. Genetic analysis of these top-performing variants revealed a common mutation in a specific gene responsible for a protease enzyme, intricately linked to regulating cellulose production.

Interestingly, the genes directly involved in cellulose synthesis showed no modifications, leading researchers to hypothesize that the protease selectively degrades proteins that previously governed cellulose production. As Laurent succinctly puts it, “Without this regulation, the cell can no longer stop the process.” This unexpected twist not only deepens our understanding of bacterial behavior but opens the door to leveraging similar techniques across various bacterial species for diverse materials beyond cellulose.

The Road Ahead: Industrial Implications and Collaborations

This pioneering research represents a significant leap forward, marking the first use of such mutation techniques aimed at enhancing the production of non-protein materials through bacterial engineering. Professor Studart encapsulates this sentiment by heralding the achievement as a “milestone” in the evolving interplay between synthetic biology and material science. With a patent application in progress for both the innovative approach and the newly mutated bacterial variants, the team is eager to collaborate with industry players focused on bacterial cellulose applications.

What was once reserved for conventional manufacturing now holds the potential for a bio-fueled renaissance, where harnessing the natural efficiencies of microorganisms can drastically redefine supply chains. But this research doesn’t merely suggest a more productive methodology; it embodies a transformative vision of sustainability, demonstrating that nature itself offers the blueprints for pioneering materials.

As this ambitious project takes shape, it may not only help accelerate the utilization of bacterial cellulose on an industrial level but also remake how we perceive the microbial world—as crucial partners in our journey toward sustainable advancement.

Leave a Reply