In recent years, the construction of dams in coastal regions has gained popularity as a strategy to combat the growing threats posed by climate change, including increasing storm intensity, saltwater encroachment, and sea-level rise. However, a novel study published in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans raises critical questions about the effectiveness of these infrastructural solutions in reducing flood risks. Instead of functioning as reliable barriers against flooding, dams might inadvertently contribute to more severe flooding events in coastal estuaries. This article delves into the complexities of this relationship by examining the nuanced findings of the study, implications for coastal management, and the broader context of climate change adaptation strategies.

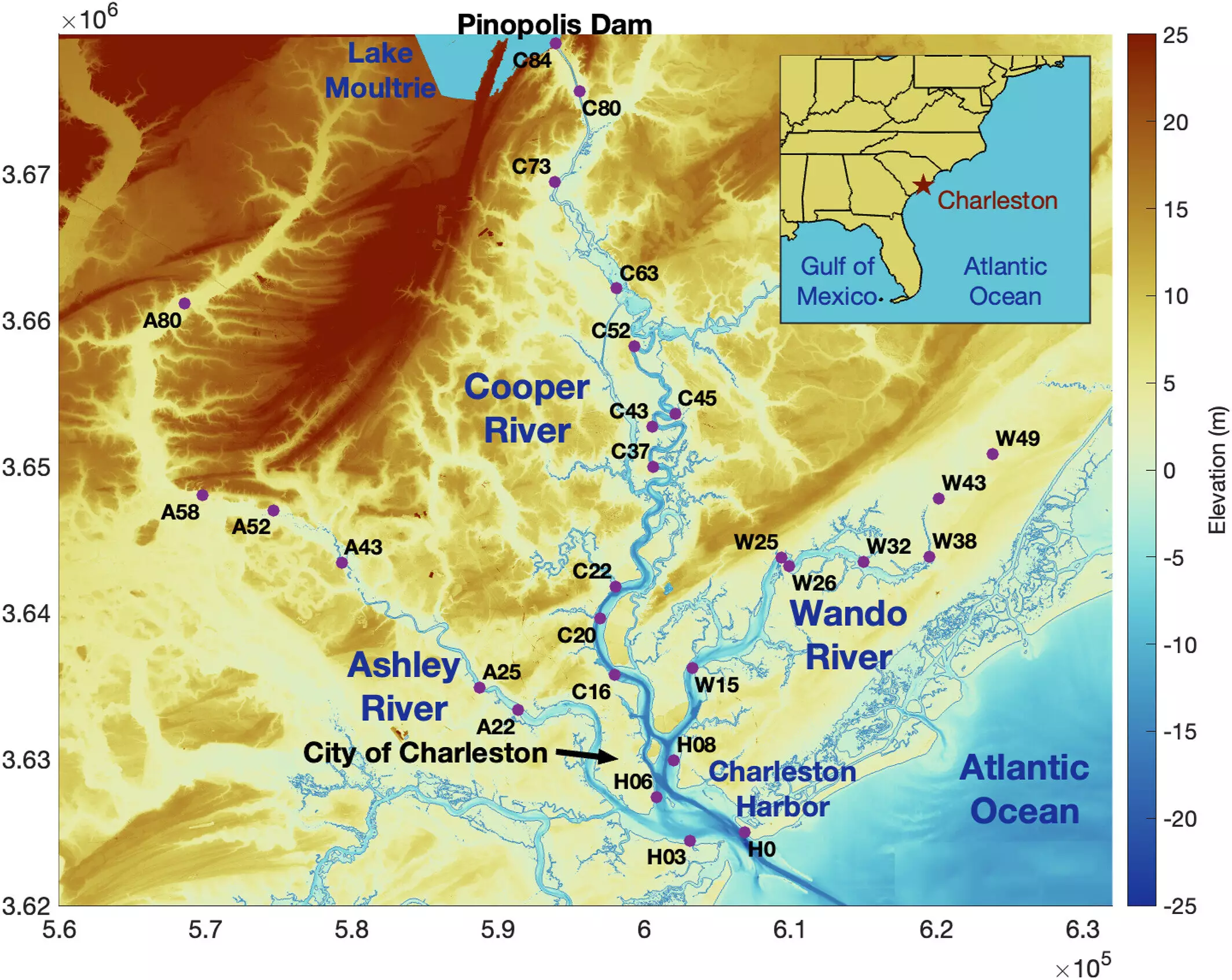

At first glance, blocking the flow of river water into the ocean seems like a prudent way to mitigate flooding risks. However, research led by Steven Dykstra, an assistant professor at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, indicates that the dynamics of water movements in coastal estuaries can be far more complex. The study utilized data from Charleston Harbor, South Carolina over a century to reveal that the effectiveness of dams in reducing flood risks varies significantly based on several factors, including surge duration and water flow dynamics.

Dykstra’s findings illustrate that estuaries, typically shaped like funnels, can exacerbate instead of ameliorate flooding conditions. The introduction of dams creates artificial boundaries that modify the natural flow of both riverine and ocean waters. This alteration can lead to an amplification of storm surges, particularly in conditions when specific wave patterns converge. Such paradoxical outcomes pose serious questions about the underlying assumptions informing coastal flood risk management.

What should be apparent from Dykstra’s research is that the shape and dimension of estuaries play a pivotal role in understanding the flow of water. By treating the enhanced wave action in confined spaces akin to water splashes in a bathtub, it becomes clear that smaller, quicker surges can lead to significant overflow under certain conditions. The research team utilized computer models to analyze the flood responses of 23 diverse estuaries, illustrating that both artificial and natural water systems display behavior influenced heavily by geographic configurations.

This understanding is paramount, as it underscores that flood risks tied to human-made barriers can extend far beyond the immediate regions where these structures are located. For instance, the study found that significant storm surges could impact areas more than 50 miles away from coastal dams, revealing the pervasive influence of constructed environments on far-flung ecosystems and communities.

The findings of this study necessitate a paradigm shift in how coastal regions approach infrastructure planning. While it is common to view dams as protective structures, this new evidence suggests that such assumptions may be misguided. Policymakers and urban planners must reconsider the efficacy of levees and dams in relation to the unpredictable nature of climate change. The intricate interplay between geology, hydrodynamics, and built environments necessitates a more holistic approach to flood risk management.

Coastal communities are now faced with the dual challenge of climate adaptation and mitigation strategies. Addressing the looming threats of flooding calls for an examination of integrated approaches that prioritize ecological health. This might include considering natural water retention systems, wetlands restoration, and fostering community resilience instead of merely relying on built infrastructure.

As the academic community continues to explore the implications of human interventions in estuarine environments, it is vital that this new understanding informed by Dykstra’s study is integrated into the conversation around climate adaptation. Progress requires a balance between innovation in engineering and respect for natural processes. The need for comprehensive risk assessments and interdisciplinary collaboration among scientists, engineers, urban planners, and local communities has never been more urgent. As climate change continues to transform coastlines, we must adopt a flexible approach that allows for continual learning and adaptation, ensuring that our strategies genuinely minimize flood risks rather than complicate them.

Leave a Reply